Marine Corps News

Trump reveals US helicopter pilots were wounded in Maduro raid

The president also said one of the soldiers who helped capture Maduro will receive the Medal of Honor.

FORT BRAGG, N.C. — President Donald Trump on Friday for the first time publicly revealed the nature of the injuries suffered by U.S. personnel in the daring raid to seize Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro and his wife from their Caracas home.

Operation Absolute Resolve — which involved more than 200 forces and 150 aircraft — left American helicopter pilots wounded “pretty bad in the legs,” Trump said during an address to troops at Fort Bragg, a major Army installation in North Carolina.

Trump explained that the pilots landed on a “couple of machine gunners” who made it through a “thicket of bombs,” before adding: “but they were taken out rapidly by our snipers who were stationed on platforms.”

During his remarks, Trump told the service members that “no other country has the extraordinary warriors that we have.”

“With your help,” the commander in chief noted, “America is winning again, America is respected again, and perhaps most importantly, we are feared by the enemies all over the globe.”

Troops erupted in applause when first lady Melania Trump took the podium to offer brief remarks. “To our great armed forces of the United States stationed all over the world, I have a nostalgia-filled message,” she said with a smile. “Happy Valentine’s Day.”

The base is home to the XVIII Airborne Corps and the Army’s Special Operations command.

After their speeches, the president and first lady privately met with the members of the Delta Force team who conducted the mission, a White House official told Military Times.

Trump, speaking to reporters before boarding Air Force One en route to Mar-a-Lago, said one of the soldiers who helped capture Maduro will receive the Medal of Honor. He did not identify the service member.

“These are great warriors. These are great patriots,” he concluded.

‘Reduced to atoms’: The devastating 1945 Allied bombing campaign in Dresden

The bombing of Dresden remains a controversial period in the Allied air war over Europe.

For 15 hours beginning on the night of Feb. 13, 1945, the historic city of Dresden, celebrated as the “German Florence” was battered by Allied warplanes.

Until that date, Germany’s seventh largest city with its 600,000 inhabitants — and roughly 700,000 refugees — had emerged from the Allied bombing campaign of World War II relatively unscathed.

The United States Army Air Force had bombed it twice — once in early October 1944 and again three months later, but even those attacks were considered relatively mild in comparison to the German cities of Berlin, Hamburg and Cologne, each of which had suffered repeated air raids throughout the war.

But in the wake of the Yalta Conference and as Soviet troops pushed deeper into eastern Germany, Allied focus began to concentrate on Dresden — in addition to its neighboring cities of Chemnitz and Leipzig — in the hopes of forcing capitulation.

The British were first to strike, as the Americans, while combating uncooperative weather, could not attack in tandem with their Anglo allies. That meant the British, under Air Marshal Arthur Harris, head of the RAF’s Bomber Command, would be the first to strike, according to the National World War II Museum.

Beginning at 10:15 p.m., unchallenged Lancaster bombers began to drop a deadly combination of high-explosive bombs and incendiaries on the city. Virtually unchallenged by either the Luftwaffe or antiaircraft guns, the low-level altitude of the bombers allowed for a careful, more precise lethality.

Within 15 minutes, 880 tons of bombs were unleashed on a city made of brick, sandstone and dry wood.

“The high-explosive weapons shattered windows, gouged out craters in the streets, and flattened walls. Firefighters were forced to take cover. The bombs also set in motion waves of high-pressure air,” according to the museum.

Small fires began to alight across the city center, soon amassing into a large, deadly conflagration.

“The thundering fire reminded me of the biblical catastrophes that I had heard about in my education in the humanities,” 18-year-old Götz Bergander would later write. “I was aghast. I can’t describe seeing this city burn in any other way. The color had changed as well. It was no longer pinkish-red. The fire had become a furious white and yellow, and the sky was just one massive mountain of cloud.”

As firefighters desperately battled the blaze, a second wave of British aircraft appeared on the horizon.

Made up of 550 heavy bombers — more than twice the size of the original formation — hell was once more unleaded.

“People’s shoes melted into the hot asphalt of the streets, and the fire moved so swiftly that many were reduced to atoms before they had time to remove their shoes,” writes historian Donald Miller in “Masters of the Air.”

“The fire melted iron and steel, turned stone into powder, and caused trees to explode from the heat of their own resin. People running from the fire could feel its heat through their backs, burning their lungs.”

The agony of the devastation also belied a chilling statistic: nearly 70% of the victims from the attack, according to Miller, suffocated from carbon monoxide poisoning.

Dresden resident Hans Schröter, whose ultimate fate remains unknown, wrote to his neighbor’s daughter on Aug. 5, 1945:

With the second attack, the door of #38 was destroyed, so that only the emergency exit for 40 and 42 was left. As we got to #40, the flames from the stairwell hit us in the face, so to save our lives we moved with haste… To get through the exit required great courage, which many could not seem to muster, and perhaps this was the case with your parents. They thought, perhaps, we would survive in the cellar, but didn’t factor in running out of oxygen. When I ran out, I saw my wife and son standing in Marienstrasse 42 so helplessly, but I had an older aunt from Liegnitz, and I wanted to save her, so I said to my wife, I’ll be back in 2 minutes. But when we came back in just that amount of time, my loved ones had disappeared, and I searched for them in the cellar, on the street — they were nowhere to be found. Everything was in flames, it wasn’t possible to get through, and since I couldn’t find my family, I summoned once more the little bit of courage that I had and went over to the Bismarck memorial and waited an hour across from the little house until the roof caved in. Then I went 30 meters along the Ringstrasse and waited there until daylight, and everything that you saw was so gruesome that you can’t describe it, everything was covered with burned corpses.

I went with great haste to my home and office, to find my loves still living, but that didn’t happen. They lay on the street in front of house 38, so peaceful, as if they slept.”

But for the residents of Dresden, Feb. 13 was just the beginning of the apocalyptic conditions.

At noon the following day more than 300 B-17 Flying Fortresses from the U.S. Eighth Air Force struck Dresden.

Battling through the haze of smoke still shooting 15,000 feet into the sky from the night prior, the Americans struck the city’s marshaling yard and, due to poor visibility, some still-reeling residential areas.

Erich Hampe, the general of technical troops who was sent from Berlin on the morning of Feb. 14 to reestablish rail communications, found the burnt-out area of Dresden utterly deserted save a llama which had escaped from the Dresden zoo, historian Richard Overy recounts in his book “The Bombers and the Bombed.”

Kurt Vonnegut and Gifford Doxsee, young infantrymen who had been captured two months earlier in the Battle of the Bulge, were part of a 150-POW labor detachment working in Dresden at the time of the bombings.

Vonnegut, who sheltered in a slaughterhouse with the address Schlachthof 5 (Slaughterhouse-Five), recounted the seminal event in a letter to his family.

“On about February 14th the Americans came over, followed by the R.A.F., their combined labors killed 250,000 people in 24 hours and destroyed all of Dresden — possibly the world’s most beautiful city. But not me.”

“The armada of U.S. Air Force planes pounded Dresden in the most intensive bombing of any single city anywhere in the world, ever, that night,” Doxsee wrote in an 18-page, single-spaced letter. “After the all-clear sounded, toward 3 a.m. on Wednesday morning, Feb. 14, 1945, our guards roused us again and forced us to climb back up to ground level. There we beheld another never-to-be-forgotten spectacle: the entire city of Dresden burning around us in all directions.”

For the third day and in a fourth raid, Dresden was hit. Originally sent to destroy an oil plant in the proximity of Leipzig, more than 200 American B-17s pivoted to their secondary target of Dresden after poor weather precluded the attack.

“The marshaling yards were not hit,” writes the museum. “The same could not be said about residential areas.”

By mid-March of that year, a Dresden police report counted 18,375 confirmed dead but estimated that figure to be much larger on account of an untold number of bodies simply liquifying from the earth. A 2004 historical commission set up by the mayor of Dresden estimated the final figure to be closer to 25,000 dead.

To avoid a health crisis, bodies that had not already been incinerated in the blasts were set in large pyres and burned.

Out of 220,000 homes in Dresden, 75,000 were totally destroyed and 18,500 severely damaged, according to Overy. Eighteen million cubic meters lay in rubble. Of the 600,000 inhabitants and an untold number of war refugees, only 369,000 remained.

Since the bombs first fell, significant controversy has arisen regarding the military necessity of the attack, with numerous postwar postmortem analyses. At the time, even British Prime Minister Winston Churchill questioned its morality.

In a letter to Air Marshal Charles Portal dated March 28, 1945, Churchill wrote: “It seems to me that the moment has come when the question of bombing of German cities simply for the sake of increasing the terror, though under other pretexts, should be reviewed.

“The destruction of Dresden remains a serious query against the conduct of Allied bombing.”

That hesitancy came perhaps too late, however, as the city was subjected to two further heavy aerial attacks by 406 B-17s on March 2 and by 580 B-17s on April 17, leaving an additional 453 dead.

Judge dismisses deportation case for Mexican father of 3 US Marines

The Department of Homeland Security said Thursday that it would appeal the judge’s decision.

An immigration judge has dismissed the deportation case against a landscaper who was arrested in Southern California last year, and the father of three U.S. Marines is now on a path toward legal permanent residency in the U.S.

The June detention of Narciso Barranco, who came to the U.S. from Mexico in the 1990s but does not have legal status, caught widespread attention as the crackdown on immigration by President Donald Trump’s administration drew scrutiny and protests.

Witnesses uploaded videos of the arrest in Santa Ana, a city in Orange County. Federal agents struggled with Barranco and pinned him to the ground outside an IHOP restaurant where he had been clearing weeds.

Barranco was taken to a Los Angeles detention center and placed in deportation proceedings. In July, he was released on a $3,000 bond and ordered to wear an ankle monitor.

In a Jan. 28 order terminating the deportation case, Judge Kristin S. Piepmeier said that Barranco, 49, had provided evidence that he was the father of three U.S.-born sons in the military, making him eligible to seek lawful status.

“I feel happy,” Barranco said in a phone interview in Spanish. “Thank God I don’t have that weight on top of me.”

Barranco said he is still staying mostly at home and not taking any chances going out until his legal paperwork has been finalized.

The Department of Homeland Security said Thursday that it would appeal the judge’s decision, which was first reported by the New York Times.

Barranco’s lawyer Lisa Ramirez said her client feels “extreme relief” now that immigration officers have removed his ankle monitor and discontinued his check-ins.

“The aggressive nature of the apprehension, it was traumatic,” Ramirez said Thursday. “Mr. Barranco has had zero criminal history. They came after him because he was a brown gardener in the streets of Santa Ana.”

Ramirez said Barranco has applied for Parole in Place, a program that protects the parents of U.S. military personnel from deportation and helps them obtain permanent residency. If that petition is approved, Barranco will receive a work permit. She estimated the process could take six months or more.

DHS Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin reiterated previous government claims that Barranco refused to comply with commands and swung his weed trimmer at an agent.

“The agents took appropriate action and followed their training to use the minimum amount of force necessary to resolve the situation in a manner that prioritizes the safety of the public and our officers,” McLaughlin said in Thursday’s statement.

His son Alejandro Barranco told The Associated Press in June that his father did not attack anyone, had no criminal record and is kind and hardworking.

The U.S. Marine Corps veteran said the use of force was unnecessary and differed greatly from his military training. He aided the U.S. military’s evacuation of personnel and Afghan allies from Afghanistan in 2021.

Alejandro left the Marine Corps in 2023. His two brothers are currently active-duty Marines.

Woo your significant other this Valentine’s Day with the help of some WWII acronyms

Let your partner know how you really feel with acronyms such as MALAYA: My Ardent Lips Await Your Arrival.

For those who are romantically inclined to celebrate Valentine’s Day this weekend, skip the tired “Be Mine” cards and really woo your significant other with some historic, bawdy acronyms.

Drawing on inspiration from World War II letters, let your partner know how you really feel with acronyms such as MALAYA: My Ardent Lips Await Your Arrival or, if you’re feeling bold, BURMA: Be Undressed/Upstairs Ready My Angel.

During the war, “so many letters were being written, they were taking up space in much needed wartime transport,” Judy Barrett Litoff, a history professor at Bryant University, told History.com. “In order to address this problem, what the government did was encourage Americans to write V-mails.”

Written on one side of an 8-by-11½-inch card, soldiers and their loved ones got around the new size restrictions by using inventive acronyms to get their ardor across.

While wartime restrictions no longer apply, if putting pen to paper to express your feelings is difficult for you, these handy acronyms are sure to do the trick.

If you are feeling poetic, however, and you want to eschew pithy messages, you can take a page out of soldier Chris Barker’s book and skip the acronyms altogether and go straight for the direct approach.

Sailing to Athens on Oct. 27, 1944, Barker told his partner, Bessie, in no uncertain terms exactly what he wished to do to her in this NSFW letter. (Page 320. You’re welcome.)

And, if your guy or gal is anything like Bessie — who wrote back “Darling, I have no complaints about your letters, I am too happy that it is my body that you want, that occupies your thoughts”— then your heartfelt letter is sure to be well received.

If you’re looking for further inspiration, here’s a helpful cheat sheet:

FRANCE: Friendship Remains And Never Can End

ITALY: I Trust And Love You

HOLLAND: Hope Our Love Lasts And Never Dies

SWALK: Sealed With A Loving Kiss

MALAYA: My Ardent Lips Await Your Arrival

BURMA: Be Undressed/Upstairs Ready My Angel

NORWICH: (k)Nickers Off Ready When I Come Home

VENICE: Very Excited Now I Caress Everywhere

CHINA: Come Home I’m N*ked Already

And for those who would rather be gagged with a spoon than celebrate cupid’s day, perhaps a “Dear John” letter will soothe your cold, black heart.

USS Gerald Ford the second aircraft carrier sent to Middle East: Report

The USS Gerald Ford set out on deployment in late June 2025, which means the crew will have been deployed for eight months in two weeks time.

The United States will send the world’s largest aircraft carrier to the Middle East to back up another already there, a person familiar with the plans said Friday, putting more American firepower behind President Donald Trump’s efforts to coerce Iran into a deal over its nuclear program.

The USS Gerald R. Ford’s planned deployment to the Mideast comes after Trump only days earlier suggested another round of talks with the Iranians was at hand. Those negotiations didn’t materialize as one of Tehran’s top security officials visited Oman and Qatar this week and exchanged messages with the U.S. intermediaries.

Already, Gulf Arab nations have warned any attack could spiral into another regional conflict in a Mideast still reeling from the Israel-Hamas war in the Gaza Strip.

Meanwhile, Iranians are beginning to hold 40-day mourning ceremonies for the thousands killed in Tehran’s bloody crackdown on nationwide protests last month, adding to the internal pressure faced by the sanctions-battered Islamic Republic.

The Ford’s deployment, first reported by The New York Times, will put two carriers and their accompanying warships in the region. Already, the USS Abraham Lincoln and its accompanying guided-missile destroyers are in the Arabian Sea.

The person who spoke to The Associated Press on the deployment did so on condition of anonymity to discuss military movements.

Ford had been part of Venezuela strike force

It marks a quick turnaround for the Ford, which Trump sent from the Mediterranean Sea to the Caribbean last October as the administration build up a huge military presence in the lead-up to the surprise raid last month that captured then-Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

It also appears to be at odds with Trump’s national security strategy, which put an emphasis on the Western Hemisphere over other parts of the world.

Trump on Thursday warned Iran that failure to reach a deal with his administration would be “very traumatic.” Iran and the United States held indirect talks in Oman last week.

“I guess over the next month, something like that,” Trump said in response to a question about his timeline for striking a deal with Iran on its nuclear program. “It should happen quickly. They should agree very quickly.”

Trump told Axios earlier this week that he was considering sending a second carrier strike group to the Middle East.

Trump held lengthy talks with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on Wednesday and said he insisted to Israel’s leader that negotiations with Iran needed to continue. Netanyahu is urging the administration to press Tehran to scale back its ballistic missile program and end its support for militant groups such as Hamas and Hezbollah as part of any deal.

The USS Ford set out on deployment in late June 2025, which means the crew will have been deployed for eight months in two weeks time. While it is unclear how long the ship will remain in the Middle East, the move sets the crew up for an usually long deployment.

The White House didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Ford’s deployment comes as Iran mourns

Iran at home faces still-simmering anger over its wide-ranging suppression of all dissent in the Islamic Republic. That rage may intensify in the coming days as families of the dead begin marking the traditional 40-day mourning for the loved ones. Already, online videos have shown mourners gathering in different parts of the country, holding portraits of their dead.

One video purported to show mourners at a graveyard in Iran’s Razavi Khorasan province, home to Mashhad, on Thursday. There, with a large portable speaker, people sang the patriotic song “Ey Iran,” which dates to 1940s Iran under the rule of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. While initially banned after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Iran’s theocratic government has played it to drum up support.

“Oh Iran, a land of full of jewels, your soil is full of art,” they sang. “May evil wishes be far from you. May you live eternal. Oh enemy, if you are a piece of granite, I am iron.”

Health care access a top complaint among troops, top enlisted leaders tell lawmakers

A Democratic senator also questioned whether the services are doing everything they can to increase child care slots.

Top senior enlisted leaders for the Air Force, Army, Marine Corps, Navy and Space Force told lawmakers Wednesday that access to health care is the most substantive complaint they’re hearing lately from their troops.

During a hearing on quality-of-life issues before the Senate Armed Services Committee’s personnel subcommittee, Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force David Wolfe cited a lack of available appointments for health care, and problems with Tricare’s reimbursement rates for health care providers in communities.

“What we’ve all seen over the length of our careers is a gradual erosion in the availability of that health care for our service members and their families,” Wolfe said.

This has been an issue for years, and problems with health care access have been exacerbated by new Tricare contracts implemented last year.

In spite of the time, effort and money spent on improving quality of life for service members and their families, “when you get down to the tactical level, there’s a gap,” said Chief Master Sergeant of the Space Force John Bentivegna. “They’re not feeling it day to day. They’re not feeling it around the kitchen table. They’re not feeling it when they call to get an appointment. They’re not feeling it when they try to get child care.”

The enlisted leaders talked about a range of issues, including their concerns about suicide and mental health, improvements to barracks, child care availability and uncertainty about pay related to federal shutdowns.

The services and the Defense Department have been working to increase child care slots. But Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., raised concerns about the persistent and long waitlists for military child care, citing waitlists of 7,800 children at the end of 2025.

“When I come back to ask these questions a year from now, are we still going to have a waitlist that’s 7,800 babies long?” she asked.

Warren contends the services haven’t done enough to attract and keep child care workers. The attrition rate is about 50% for child care workers in military child development centers, Warren said, and she criticized the Army, Navy and Air Force for not upgrading the pay scales by April 2025 as required by law.

When asked why they leave, workers say it’s low pay, according to Warren.

“You have the tools from Congress. We’ve already given them to you and you haven’t picked them up and used them,” she said.

However, Wolfe and Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy John Perryman said they’ve been told that their services have already upgraded their pay scales, and it has made a difference in the staffing.

“We have moved out with [using] the authorities. We are making significant progress in reducing our waitlist,” Perryman said, while noting it’s not okay to have 1,400 children still waiting for care.

“Right now, we’ve got about 2,700 [children] with unmet need across the Air Force. And that’s absolutely not where we want to be,” Wolfe said. “We are committed to making sure that this number goes down over time and does not creep back up.”

But Warren said parents don’t have time to wait. “They don’t have a year that they can just set aside while they’re waiting around on a 1,400 or 2,700 waitlist. They’ve got to have child care now.”

To the Space Force and Marine Corps, she said, “You nailed it. And let’s keep it up because that’s what we’ve got to do.

“We can’t say that we are a military that cares about our families if we pretend to provide child care and then we’ve got a waitlist that’s got 7,800 babies waiting on it.”

Virginia Supreme Court rules US Marine’s adoption of Afghan war orphan will stand

A U.S. Marine and his wife will keep an Afghan orphan they brought home in defiance of a U.S. government decision to reunite her with her Afghan family.

The Virginia Supreme Court ruled Thursday that a U.S. Marine and his wife will keep an Afghan orphan they brought home in defiance of a U.S. government decision to reunite her with her Afghan family. The decision likely ends a bitter, yearslong legal battle over the girl’s fate.

In 2020, a judge in Fluvanna County, Virginia, granted Joshua and Stephanie Mast an adoption of the child, who was then 7,000 miles away in Afghanistan living with a family the Afghan government decided were her relatives.

Four justices on the Virginia Supreme Court on Thursday signed onto an opinion reversing two lower courts’ rulings that found the adoption was so flawed it was void from the moment it was issued.

The justices wrote that a Virginia law that cements adoption orders after six months bars the child’s Afghan relatives from challenging the court, no matter how flawed its orders and even if the adoption was obtained by fraud.

Three justices issued a scathing dissent, calling what happened in this court “wrong,” “cancerous” and “like a house built on a rotten foundation.”

Marine who adopted Afghan orphan will stay in service

An attorney for the Masts declined to comment, citing an order from the circuit court not to discuss the details of the case publicly. Lawyers representing the Afghan family said they were not yet prepared to comment.

The child was injured on the battlefield in Afghanistan in September 2019 when U.S. soldiers raided a rural compound. The child’s parents and siblings were killed. Soldiers brought her to a hospital at an American military base.

The raid was targeting terrorists who had come into Afghanistan from a neighboring country; some believed she was not Afghan and tried to make a case for bringing her to the U.S. But the State Department, under President Donald Trump’s first administration, insisted the U.S. was obligated under international law to work with the Afghan government and the International Committee of the Red Cross to unite the child with her closest surviving relatives.

The Afghan government determined she was Afghan and vetted a man who claimed to be her uncle. The U.S. government agreed and brought her to the family. The uncle chose to give her to his son and his new wife, who raised her for 18 months in Afghanistan.

Meanwhile, Mast and his wife convinced courts in rural Fluvanna County, Virginia, to grant them custody and then a series of adoption orders, continuing to claim she was the “stateless” daughter of foreign fighters.

Judge Richard Moore granted them a final adoption in December 2020. When the six-month statute of limitations ran out, the child was still in Afghanistan living with her relatives, who testified they had no idea a judge was giving the girl to another family. Mast contacted them through intermediaries and tried to get them to send the girl to the U.S. for medical treatment but they refused to let her go alone.

When the U.S. military withdrew from Afghanistan and the Taliban took over, the family agreed to leave and Mast worked his military contacts to get them on an evacuation flight. Mast then took the baby from them at a refugee resettlement center in Virginia, and they haven’t seen her since.

The AP agreed not to name the Afghan couple because they fear their families in Afghanistan might face retaliation from the Taliban. The circuit court issued a protective order shielding their identities.

The Afghans challenged the adoption, claiming the court had no authority over a foreign child and the adoption orders were based on Mast repeatedly misleading the judge.

The Virginia Supreme Court on Thursday wrote that the law prohibiting challenges to an adoption after six months is designed to create permanency, so a child is not bounced from one home to another. The only way to undercut it is to argue that a parent’s constitutional rights were violated.

The lower courts had found that the Afghan couple had a right to challenge the adoption because they were the girl’s “de facto” parents when they came to the United States.

Four of the Supreme Court judges — D. Arthur Kelsey, Stephen R. McCullough, Teresa M. Chafin, Wesley G. Russell Jr. — disagreed.

“We find no legal merit” in the argument that “that they were ‘de facto’ parents of the child and that no American court could constitutionally sever that relationship,” they wrote. They pointed to Fluvanna County Circuit Court Judge Richard Moore’s findings that the Afghan couple “are not and never were parents” of the child, because they had no order from an Afghan court and had not proven any biological relationship to her.

The Afghans had refused DNA testing, saying it could not reliably prove a familial connection between opposite-gender half-cousins. They insisted that it didn’t matter, because Afghanistan claimed the girl as its citizen and got to determine her next-of-kin.

The Supreme Court leaned heavily on a 38-page document written by Judge Moore, who granted the adoption, then presided over a dozen hearings after the Afghans challenged it. He wrote that he trusted the Masts more than the Afghans, and believed that the Masts’ motivations were noble while the Afghans were misrepresenting their relationship to the child.

The Supreme Court also dismissed the federal government’s long insistence that Trump’s first administration had made a foreign policy decision to unite her with her Afghan relatives, and a court in Virginia has no authority to undo it. The government submitted filings in court predicting dire outcomes if the baby was allowed to remain with the Marine: it could be viewed as “endorsing an act of international child abduction,” threaten international security pacts and be used as propaganda by Islamic extremists — potentially endangering U.S soldiers overseas.

But the Justice Department in Trump’s second administration abruptly changed course.

The Supreme Court noted in its opinion that the Justice Department had been granted permission to make arguments in the case, but withdrew its request to do so on the morning of oral arguments last year, saying it “has now had an opportunity to reevaluate its position in this case.”

The Supreme Court returned repeatedly to Moore’s finding that giving the girl to the family “was not a decision the United States initiated, but rather consented to or acquiesced in.”

The three judges who dissented were unsparing in their criticism of both the Masts and the circuit court that granted him the adoption.

“A dispassionate review of this case reveals a scenario suffused with arrogance and privilege. Worse, it appears to have worked,” begins the dissent, written by Justice Thomas P. Mann, and signed by Chief Justice Cleo E. Powell and LeRoy F. Millette, Jr.

A Virginia court never had the right to give the child to the Masts, the dissent said.

They castigated the Masts for “brazenly” misleading the courts during their quest to adopt the girl.

“We must recognize what an adoption really is: the severance and termination of the rights naturally flowing to an otherwise legitimate claimant to parental authority. Of course, the process must be impeccable. An evolved society could not sanction anything less than that. And here, it was less,” Mann wrote. “If this process was represented by a straight line, (the Masts) went above it, under it, around it, and then blasted right through it until there was no line at all — just fragments collapsing into a cavity.”

No evidence women in combat roles lower standards, top enlisted leaders say

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s call for a review of the effectiveness of women in combat roles prompted questions during a Senate Armed Services hearing.

Top enlisted leaders from each service told lawmakers Wednesday that they support women serving in any role in the military, including combat arms, if they meet the established standards.

Enlisted leaders from the five services, as well as the senior enlisted adviser to the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, added that they have yet to see any indication that women serving in combat units have caused standards to lower.

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s recent call for a review of the effectiveness of women in combat roles prompted Sen. Mazie Hirono, D-Hawaii, to question the service leaders during a Senate Armed Services personnel subcommittee hearing.

“This is an attack on women to call for this kind of review,” Hirono said during the hearing focusing on troops’ quality of life. “I think that he is laying the groundwork to reverse the policy allowing women to serve in combat arms positions.”

Hirono added that she plans to introduce legislation to codify the DOD policy allowing women to serve in combat arms positions as long as they meet required standards.

The six-month assessment, first reported by NPR in January, requires the Army and Marine Corps to submit data to assess the operational effectiveness of ground combat units. It will also analyze how women have integrated into these ground combat roles over the span of more than a decade.

“I’ve seen no data that supports that there is any lowering of standards or that there’s lowering of the readiness of units with those females in the units,” Navy Master Chief David L. Isom, senior enlisted adviser to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said at the hearing.

“I’m not seeing anything that leads me to believe there’s an issue with meeting the standard or affecting readiness,” Sergeant Major of the Army Michael Weimer added.

Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force David Wolfe said he has served with “some of the best warfighters that the world has ever known” in the Air Force. “Some of them happen to be men, some of them happen to be women. Absolutely not, I’ve not seen any erosion.”

From the Space Force, the service’s Chief Master Sgt. John Bentivegna noted that “we have not seen any erosion in the readiness based on any of the administration’s positions.”

Hegseth’s review, Hirono added, “undermines the sacrifice of thousands of female service members who have already met the rigorous gender neutral standards and have served in combat with distinction.”

She said everyone who wants to serve their country should have the opportunity to do so, to include LGBTQ members.

A Medal of Honor recipient rescued a downed pilot in WWI. The airman’s identity remained a mystery — until now.

Ralyn M. Hill put his life on the line for a downed ally.

War has a way of changing the lives of its participants. Sometimes, it puts the main actor through a moment of decision that leads to an extraordinary feat. In the case of Ralyn Hill, it involved rushing where the average soldier would fear to tread, simply to retrieve a complete stranger from the jaws of death.

Hill was born in Lindenwood, Illinois, on May 6, 1899. After the United States declared war against Germany on April 6, 1917, he enlisted in the Illinois National Guard and after training shipped out with Company H, 129th Infantry Regiment, 33rd “Prairie” Division.

Once in France, the division underwent a temporary break. Although General John J. Pershing insisted that the American Expeditionary Forces be held together as entity, he and the British command were persuaded by Lt. Gen. John Monash, commander of I Australian Corps, to lend two elements for his assault on Hamel, Somme, France. Much, no doubt to Hill’s and his comrades’ chagrin, the 130nd and 131st had the honor of having their combat debut alongside the Aussies on July 4 — an added touch of timing deliberately chosen by Monash. The result was a swift victory that demonstrated Monash’s brilliant use of combined arms and established a working relationship between Yank and Digger that has lasted more than a century.

The 131st Infantry went on to play a distinguished role alongside the Australians at Chipilly Ridge and Amiens on Aug. 9. Then, as promised to Pershing, on Aug. 23 the 33rd Division was reunited and sent to the Toul sector. Within the division, the 65th Infantry Brigade was organized around the 129th and 130th Infantry Regiments and the 124th Machine Gun Battalion.

After successfully concluding its first major offensive at St. Mihiel on Sept. 18, 1918, the AEF launched a more ambitious push into the Argonne Forest on Sept. 26. There, facing the Meuse River and facing thickly and forested terrain beyond, the Americans encountered their first serious opposition — the German Fifth Army. During the grueling six-week campaign that followed, well-entrenched German forces inflicted heavy casualties on a succession of AEF divisions.

On Oct. 7 the 129th Infantry was fighting around Dannevoux Hill, now a corporal, was observing the area when circumstances called him to extraordinary action, as summed up in his citation:

“Seeing a French biplane fall out of control on the enemy side of the Meuse with its pilot injured, Cpl. Hill voluntarily dashed across the footbridge to the side of the wounded man and, taking him on his back, started back to his lines. During the entire exploit he was subjected to murderous fire of enemy machine guns and artillery, but he successfully accomplished his mission and brought his many to a place of safety, a distance of several hundred yards.”

Hill went on to survive the war and on April 22, 1919, at Ettelbruck, Luxembourg, he stood before Gen. Pershing to receive the Medal of Honor.

Although there is no doubting Hill’s courageous deed, events surrounding it suggest some discrepancies. First, the “French” airplane was made in France, but French records for Oct. 7 indicate no losses. That morning, however, as the 103rd Aero Squadron, U.S. Army Air Service, was returning from a mission, it lost contact with one of its French-built Spad XIII fighters, last seen at about 11 a.m. and declared “missing in action” as of 12:30.

The pilot, 2nd Lt. Wellford MacFadden Jr., was identified and buried two miles west of Brieulles, opposite the 4th Division. His grave was later rediscovered by Capt. Friedrich Wilhelm Zinn, a former observer in French escadrille Sop.24 and pioneer in accounting for USAS losses under the principle of “leave no man behind.”

What all this information, allowing for inconsistencies, suggests that MacFadden had probably fallen afoul of German ground fire (the German fighters made no claims that day), had crashed in German lines and was subsequently recovered by Hill. MacFadden died shortly afterward from his injuries, which in no way discredits Hill’s effort to bring him back, dead or alive.

After the war, Hill made a career of law enforcement, as a sergeant deputy sheriff in Oregon, Illinois, and an officer in Abilene, Kansas. He married Iva Fern Rock and had three daughters: Pauline Murphy, Shirley J. Patterson and Mary Ellen Reynolds. Ralyn M. Hill died on March 25, 1977 and was buried in Abilene.

Syria says its forces have taken over al-Tanf base after handover from US

The military outpost was run for years by U.S. troops as part of the war against the Islamic State group.

DAMASCUS, Syria — Syrian government forces have taken control of a base in the east of the country that was run for years by U.S. troops as part of the war against the Islamic State group, the Defense Ministry said in a statement Thursday.

The al-Tanf base sits on a strategic location close to the borders with Jordan and Iraq. In a terse statement, the Syrian Defense Ministry said the handover of the base took place in coordination with the U.S. military and Syrian forces are now “securing the base and its perimeters.”

The U.S. Central Command said in a statement that troops have completed “the orderly departure” from al-Tanf base on Wednesday.

It said that the Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve, established by the U.S. Central Command in 2014, has advised, assisted and enabled partner forces in the fight against IS. It added that in April last year, the Defense Department announced the U.S. military would begin consolidating its locations in Syria after the territorial defeat of IS almost seven years ago.

“U.S. forces remain poised to respond to any IS threats that arise in the region as we support partner-led efforts to prevent the terrorist network’s resurgence,” said Adm. Brad Cooper, CENTCOM commander. “Maintaining pressure on ISIS is essential to protecting the U.S. homeland and strengthening regional security.”

The command said that over the past two months, U.S. forces have struck more than 100 targets with over 350 precision munitions while capturing or killing more than 50 IS members.

The Syrian Defense Ministry also said that Syrian troops are now in place in the desert area around the al-Tanf garrison, with border guards to deploy in the coming days.

The deployment of Syrian troops at al-Tanf and in the surrounding areas comes after last month’s deal between the government and the U.S.-backed and Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, or SDF, to merge into the military.

Al-Tanf garrison was repeatedly attacked over the past years with drones by Iran-backed groups but such attacks have dropped sharply following the fall of Bashar Assad’s government in Syria in December 2024 when insurgent groups marched into his seat of power in Damascus.

Syria’s interim President Ahmad al-Sharaa has been expanding his control of the country, and last month government forces captured wide parts of northeast Syria after deadly clashes with the SDF. A ceasefire was later reached between the two sides.

Al-Tanf base played a major role in the fight against the Islamic State group that declared a caliphate in large parts of Syria and Iraq in 2014. IS was defeated in Iraq in 2017 and in Syria two years later.

Over the past weeks, the U.S. military began transferring thousands of IS prisoners from prisons run by the SDF in northeastern Syria to Iraq, where they will be prosecuted.

The number of U.S. troops posted in Syria has changed over the years.

The number of U.S. troops increased to more than 2,000 after the Oct. 7, 2023, attack by Hamas in Israel, as Iranian-backed militants targeted American troops and interests in the region in response to Israel’s bombardment of Gaza.

The force has since been drawn back down to around 900.

Associated Press journalist Bassem Mroue in Beirut contributed to this report.

Two US Navy ships collide in Caribbean, leaving 2 sailors injured

The destroyer USS Truxtun and the supply ship USNS Supply collided as the warship was getting a load of supplies, leaving two troops with minor injuries.

Two Navy ships deployed as part of the Trump administration’s massive military buildup in the Caribbean Sea have collided, leaving two troops with minor injuries, U.S. Southern Command said Thursday.

The destroyer USS Truxtun and the supply ship USNS Supply collided on Wednesday as the warship was getting a new load of supplies. The maneuver typically has the vessels sailing parallel, usually within hundreds of feet, while fuel and supplies are transferred across the gap via hoses and cables.

The military statement said two personnel reported minor injuries after the collision and that both were in stable condition. The two ships now are sailing safely, according to Southern Command.

The USS Truxtun is a recent addition to the large naval presence in the Caribbean that stands at 12 ships, including the world’s largest aircraft carrier, the USS Gerald R. Ford, and several amphibious assault ships carrying thousands of Marines.

The Republican administration built up the largest military presence in the region in generations before carrying out a series of deadly strikes on alleged drug boats since September, seizing sanctioned oil tankers and conducting a surprise raid that captured Venezuela’s then-president, Nicolás Maduro.

The USS Truxtun left its home port in Norfolk, Virginia, on Feb. 3. The destroyer had to return to port for several days to conduct “an emergent equipment repair” and it ultimately set sail for the Caribbean on Feb. 6, according to a Navy official, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive operational details.

The Wall Street Journal first reported the collision, which is rare for warships. The Navy’s most recent collision occurred in February 2025 when the aircraft carrier USS Harry S. Truman collided with a merchant vessel just outside the Suez Canal near Port Said, Egypt. That resulted in minor damage to the Truman but no injuries.

An investigation released in December revealed that as the aircraft carrier was running behind schedule, the officer navigating the ship drove it at an unsafely high speed.

As a merchant ship moved into a collision path with the carrier, the officer in charge did not take enough action to move out of danger and the ship also was traveling so fast that it would have needed almost a mile and a half to come to a stop after halting the engines, the report found.

Louisiana National Guardsman leaves M4 carbine in Bourbon Street bathroom

A whole bouquet of oopsie daisies.

Beside a urinal and bin of used paper towels, an assault rifle was photographed leaning against a tiled bathroom wall in an image that spread quickly across the internet.

The M4 carbine was issued to a Louisiana National Guardsman who left it in a New Orleans bathroom this week. The weapon has since been recovered, according to a spokeswoman for the Louisiana National Guard.

The rifle was left in a Bourbon Street bathroom on Sunday, Feb. 8 and recovered the same day, Lt. Col. Noel Collins confirmed on Thursday in a statement to Military Times.

“The soldier and incident are being handled internally and the incident is under investigation,” she said.

The guardsman left the rifle in the bathroom of Lafitte Hotel and Bar, a historic inn located in the city’s French Quarter.

The person who posted the image on Reddit captioned the image, “The police are now involved but I waited for a National Guard guy to use the bathroom and then after I entered I found this assault rifle.”

The New Orleans Police Department deferred all questions to the Louisiana National Guard.

Service members are required to maintain accountability of their weapons at all times. Losing a weapon can trigger administrative consequences or re-training.

Around 350 Louisiana National Guardsmen were mobilized last December under federal Title 32 status until the end of February this year to support local law enforcement in the French Quarter for major events like New Year’s Eve, the Sugar Bowl and Mardi Gras, the Louisiana Guard reported in a press release.

Under Title 32 status, guardsmen remain under state control but are federally funded.

Marine declared lost at sea after falling overboard from the USS Iwo Jima

Rescue efforts for Lance Cpl. Chukwuemeka E. Oforah, 21, were suspended on Feb. 10, three days after the Marine went overboard in the Caribbean Sea.

A Marine who fell overboard from the amphibious assault ship USS Iwo Jima on Feb. 7 has been declared dead after exhaustive search-and-rescue efforts were unsuccessful, the service announced.

Rescue efforts for Lance Cpl. Chukwuemeka E. Oforah, 21, were suspended on Feb. 10, three days after the Marine went overboard in the Caribbean Sea, II Marine Expeditionary Force officials announced.

Oforah, of Florida, was an infantry rifleman assigned to 3rd Battalion, 6th Marines out of Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, the service announced. He graduated from Marine Corps Recruit Depot-Parris Island in February 2024 and was deployed with the 22nd Marine Expeditionary Unit at the time of his death.

“We are all grieving alongside the Oforah family,” Col. Tom Trimble, the 22nd MEU commanding officer, said in a release. “The loss of Lance Cpl. Oforah is deeply felt across the entire Navy-Marine Corps team. He will be profoundly missed, and his dedicated service will not be forgotten.”

A massive multi-branch search effort ensued on Feb. 7 after a man overboard was declared, according to the release.

Five U.S. Navy ships, a rigid-hull inflatable boat, surface rescue swimmers from the Iwo Jima and 10 aircraft from the Navy, Marine Corps and Air Force joined the search efforts, according to the announcement.

The Iwo Jima is currently deployed to the Caribbean, where it was recently involved in transporting captured Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro.

The incident is currently under investigation.

VA reorganization projected to cost at least $312 million

The reforms, known as the RISE initiative, are expected to begin this year with an aim to reduce the VHA’s administrative overhead, improve clinical care.

A planned restructuring of the Veterans Health Administration will cost an estimated $312 million over five years and require an initial investment of $521 million, according to a top congressional appropriator.

The reforms, known as the Restructure for Impact and Sustainability Effort, or RISE initiative, are expected to begin this year with an aim to reduce the VHA’s administrative overhead and improve hospital services and clinical care.

Initial VA briefings to congressional lawmakers did not include the potential costs of the restructuring, but Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz, D-Fla., said Wednesday she initially was told it would be “cost neutral.”

During a House Veterans Affairs Committee hearing, however, Wasserman Schultz, the senior Democrat on the House subcommittee that funds the VA, said the up-front costs will be more than a half billion dollars,but that would be reduced over five years to $312 million as a result of savings.

She pressed VA Secretary Doug Collins on his plans for funding, given that the department’s fiscal 2026 budget is set.

“You’re planning on doing this immediately in this fiscal year, is that correct?” Wasserman Schultz asked. “Do you expect that you’ll be sending the committee a reprogramming request for approval?”

Collins said he believed that the VA could cover the costs “inside our current authorizations for appropriations” without having to ask for extra funds or file a request to Congress.

“This is going to come out of our regular account funds. We’re just moving people here. There’s not an accounting for this in that situation,” Collins said.

In May, the VA moved $343 million from funds marked for contracts and administration to pay for outside health care without asking Congress. Reprogramming requests require detailed accounting from the department as well as approval of both the House and Senate Appropriations Committees, but Collins insisted that the shifting the funds, obtained from the closure of the VA’s diversity and inclusion offices and cancellation of hundreds of contracts, did not require such a request.

The VA notified Congress after the fact — a move that irritated both Republican and Democrat lawmakers.

“This should have come in the form of a reprogramming request,” House Appropriations Committee Chairman Tom Cole, R-Okla., said at the time. “Obviously, we have authority there and the chairman has authority there.”

On Wednesday, Wasserman Schultz asserted that the appropriations subcommittees for military construction, Veterans Affairs and related agencies is responsible for funding the VA’s reorganization and must approve any internal transfers to cover its costs.

“I look forward to the report that you are statutorily required to submit to the Appropriations Committee so we can see on paper exactly what your plan entails, including robust and appropriate justifications,” she said.

Wasserman Schultz also noted that according to a briefing she received, the VA expects to save $1.7 billion from “personnel actions” resulting from the organization — the first time a dollar amount has been announced on the potential savings of the plan.

Under the reorganization, the VA will decrease the number of Veterans Integrated Service Networks, or VISNs, which provide oversight, administrative, budgetary services and support to VA medical centers, from 18 to 5 and create health service areas, or HSAs, within the VISNs to focus on medical centers and the communities where veterans get medical care.

The VA has lost 30,000 personnel in the past year as a result of resignations, retirements and attrition, as well as plans for an additional reduction of 24,000 jobs, which officials say were mainly positions created during the COVID-19 pandemic that are no longer required and have been vacant for at least a year.

Wasserman Schultz wanted to quiz Collins on the projected personnel savings but was not given additional time for her questions, which came at the end of a two-hour hearing.

House Veterans Affairs Committee Chairman Rep. Mike Bost, D-Ill., had established a hard stop at the start of the event and held lawmakers to strict time limits during the hearing, which was marked by combative exchanges between Collins and Democrats upset by the administration’s response to the death of Minneapolis VA Medical Center nurse Alex Pretti.

Numerous Democrats took Collins to task for a social media statement he made after the killing of Pretti by federal agents.

“You lead a large organization with employees that are hurting in the wake of this killing … it would be helpful to show just some of the courage that our many veterans have shown in their service by standing up and calling out what is wrong, particularly with respect to Mr. Pretti and his life, his life’s work,” said Rep. Herb Conaway, D-N.J. “Will you stand up for him and show just a little bit of the courage that our veterans show every day?”

Collins said repeatedly throughout the hearing that he would not answer questions regarding Pretti or the investigation into his death. In response to Conaway, he bristled.

“I show the courage of a 27-year veteran sitting in front of you and will not be spoken down to. I’ve been asked and answered the question,” Collins said.

The administration has not released its proposed fiscal 2027 budget, which was due the first week of February. Collins said an updated cost estimate for the RISE initiative will be included in the budget.

“That’s being put together now,” Collins said.

Marine Corps continues streak as only service to pass financial audit

For its third consecutive year, the U.S. Marine Corps keeps its record as the first and only service to cleanly pass a financial audit.

The U.S. Marine Corps passed its fiscal year 2025 financial audit for the third year in a row, marking the Corps as the first and only service to achieve a successful audit opinion.

The Corps’ audit process revealed that the service’s financial records are accurate, complete and compliant with federal regulations, according to a Monday release.

“When the American people entrust us with their tax dollars, we owe them careful judgment and integrity in how those dollars are spent,” Commandant of the Marine Corps Gen. Eric M. Smith said in the statement.

The Corps has long been the only service to pass a “clean, unmodified audit opinion” across the military and the Department of Defense as a whole since 2018, when it was first mandated to conduct a full audit.

The Pentagon continues to struggle to achieve a clean opinion from the Inspector General as required by Congress by its FY28 deadline, which the department set on its own.

The DOD recently was allotted a budget of around $901 billion for Fiscal Year 2026, but President Donald Trump has recently called for its increase to $1.5 trillion for fiscal 2027 in a social media post last month.

“The findings produced by the audit help the service to more efficiently and accurately plan, program, budget, and spend funds appropriated by Congress,” the memo reads.

Independent public accountants contracted by the Department of Defense Inspector General audited all records, the release states.

The audit tests the Corps’ network, business systems and internal controls, while validating accurate global tracking and reporting of financial transactions, inventory of facilities, equipment and assets and accountability of taxpayer dollars spent during this last fiscal year, according to the statement.

The service strives to modernize its system and procedures to create a smoother and more efficient audit for years to come by utilizing artificial intelligence and automation, officials said in a media roundtable last week.

In the past, the service has depended on manual assessments and human reviews, but the Corps has begun moving away from human reviews to lift some of the burden.

Better technology to support the Corps’ audit practices has reduced manual effort, improved data accuracy and strengthened audit compliance through automation and control, Deputy Commandant for Programs and Resources Lt. Gen. James Adams III said in a Friday video to the force.

In the video, Adams highlighted how Marines and civilians identified inefficiencies and solutions, pointing out how one Marine developed an automation tool that cut research hours by nearly 40% and helped close the fiscal year with no unmatched transactions.

“With each additional audit year under our belts, we get smarter and adapt, finding new and better ways to get the job done,” Adams said in the memo.

The audit identified seven “material weaknesses” for the Corps to improve on going forward, but that did not stop its passing of the review, per the release.

The final report said the ongoing weaknesses are: oversight and monitoring; budget execution and monitoring; general property, plant and equipment; inventory and related property; operating materials and supplies; financial information systems — access controls/segregation of duties; financial information systems — configuration management; and financial information systems — information technology operations.

US Marine Corps advances plans for drone wingman

The Marine Corps released its 2026 Aviation Plan on Tuesday, outlining its strategy to maintain and develop its aviation fleets.

The Marine Corps has big plans in 2026 to advance toward fielding a drone wingman to collaborate with the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.

On Tuesday, the Corps released its 2026 Aviation Plan, outlining its strategy to maintain and develop its aviation fleets.

A top priority: testing and developing Marine Air-Ground Task Force Unmanned Expeditionary (MUX) TACAIR, an unmanned “collaborative combat aircraft” intended to “increase the survivability and lethality of F-35 and enable the successful execution of the [strike fighter] mission across a wide range of developing threat environments,” according to the document.

The relatively low-cost MUX TACAIR will do that by assuming some of the risk that would otherwise fall to the manned aircraft in aerial combat operations, according to the Corps’ vision for the program.

Also on Tuesday, major defense contractor General Atomics Aeronautical Systems, Inc. announced its uncrewed jet, YFQ-42A, had been selected by the Marine Corps as a candidate for the MUX TACAIR program.

“The agreement integrates GA-ASI’s expertise in autonomy and uncrewed aircraft systems with a government-provided mission package, using the YFQ-42A platform as a surrogate to evaluate integration with crewed fighters,” the company said in a release.

Next steps include installing a Marine Corps mission kit onto the drone jet for follow-on assessment and rapid development of autonomy for the mission kit, described as “a cost-effective, sensor-rich, software-defined suite capable of delivering kinetic and non-kinetic effects,” so the system can then be put through its paces in expeditionary conditions.

The announcement follows the successful maiden flight of YFQ-42A in August. The same platform has also been selected by the Air Force for testing in its CCA program.

Recent months have been eventful for the MUX TACAIR program. After demonstrating manned-unmanned teaming between the F-35 and Kratos’ XQ-58 Valkyrie drone through four experimentation flights beginning in 2024, the Marine Corps last month selected the Valkyrie for mission development as part of the program, granting a Northrop Grumman-Kratos team a $231.5 million contract for the work.

Also last month, Marine Corps Aviation formally launched the MUX TACAIR Transition Task Force to supervise and streamline the fielding process among stakeholder commands.

A first-of-its-kind task force conference kicked off Monday at Marine Corps Air Station Yuma, Arizona, focused on “cross-functional team (CFT) formation, and problem framing to the objective of future operational test flights at [Marine Test and Evaluation Squadron-1],” according to the announcement.

Five cross-functional teams will oversee aspects of the program ranging from training, readiness and operations to basing and facilities, officials said.

Upcoming project milestones for the MUX program, according to the newly released aviation plan, will include taxi testing with prototypes and a first flight for the conventional takeoff and landing variant of the drone.

Also on the to-do list is development of electronic warfare capabilities for the MUX TACAIR platforms, specifically so they can be deployed in defense of the manned platforms they escort and support.

The aviation plan adds that among key infrastructure priorities for the Corps is facilitating development and planning for MUX TACAIR “with focus on operational testing” at the air station in Yuma.

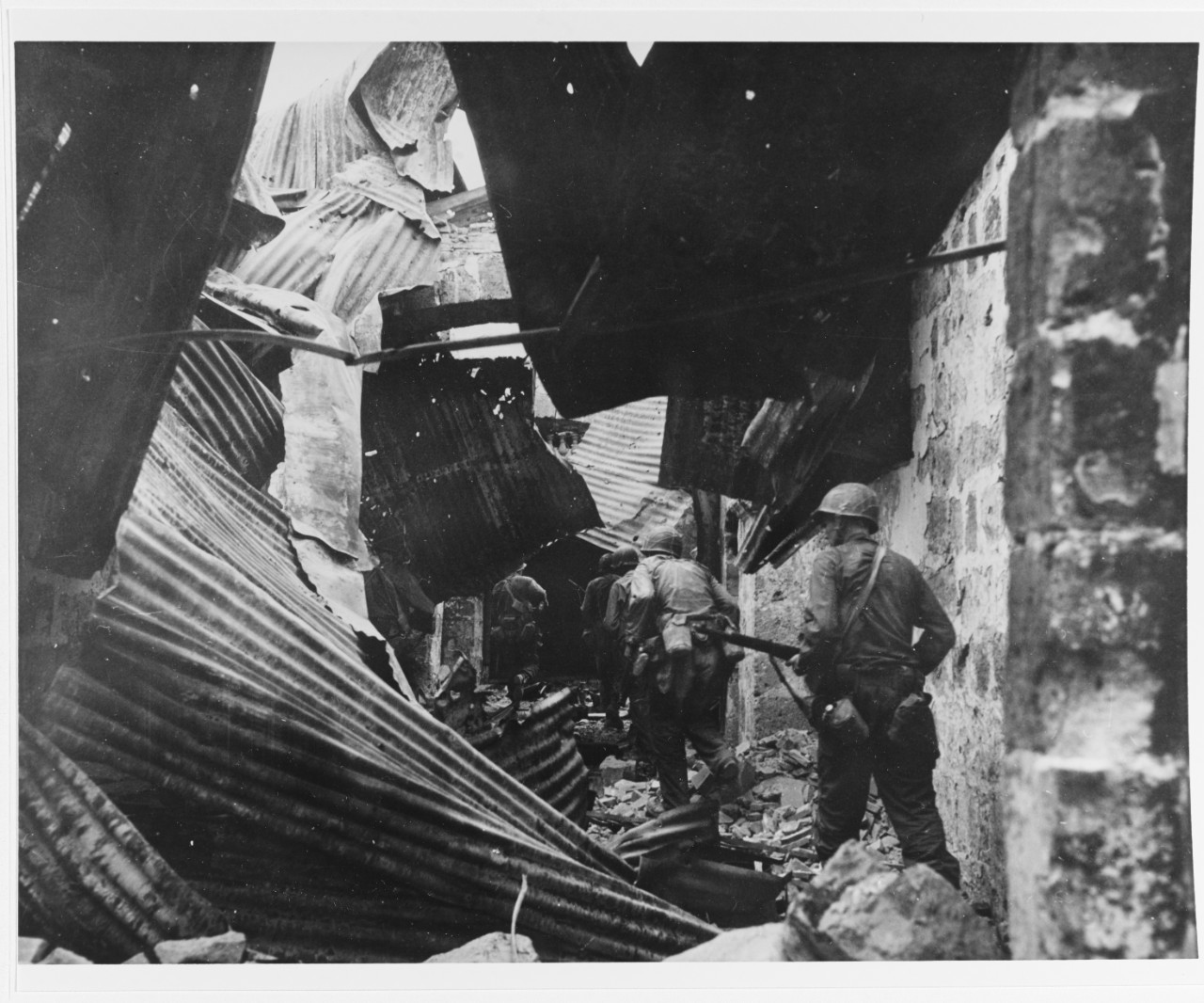

In the bloody, urban combat to liberate Manila, this airborne ‘Angel’ sacrificed all

Manuel "Toots" Pérez pinpointed what was holding up his company’s advance... and cleaned it out.

Airborne troops are extremely vulnerable when they are descending in their parachutes. To compensate, their intense combat training is designed to take charge from the moment their boots touch the ground... whatever that ground may be. One of the many cases in point is that of PFC. Manuel Pérez Jr.

Born in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, on March 3, 1923, Pérez was raised in Chicago, Illinois, after the death of his mother, Tiburcia, when he was just two years old. After graduating high school, the young Pérez worked at a time for Best Foods Inc., but in January 1943 he enlisted and, since he had not been drafted, he could choose his branch of service. For Pérez, that choice was airborne training and attachment to Company A, 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment — dubbed the “Angels” and “The Band of Brothers of the Pacific” — 11th Airborne Division.

During training at Camp Toccoa, Georgia, Pérez acquired the nickname of “Toots” from his fellow troopers for his youthful looks. He was also described as soft spoken and intense by nature, but his poor marksmanship scores at Camp Mackall, North Carolina almost led to his transfer. With help from his friends, however, he overcame his handicap enough to pass.

Regarding one of his demonstrated special talents, his platoon commander, 2nd Lt. Theodore Baughn, remarked: “His detection of the enemy was very sharp. And his reaction with weapons was very quick and effective.”

Consequently, by the time the 511th arrived at its frontline assignment, southern Luzon, Pérez was the lead scout for A Company.

On Feb. 3, 1945, the 511th PIR parachuted onto Tagaytay Ridge as part of Operation Shoestring, a series of maneuvers to slip past Japanese forces holding the Philippine capital of Manila.

The 11th Airborne Division was attached to the Sixth Army, engaged in a race against time to liberate the city before its fanatical defender, Rear Adm. Sanji Iwabuchi, destroyed it along with its populace.

It may be noted that the Japanese army commander-in-chief on Luzon, Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita, had evacuated most of his force out of the city and into the mountains in order to maintain a mobile presence for as long as possible. He had ordered Iwabuchi to do the same, but the admiral disobeyed and ignored that order. As a result, an estimated 100,000 civilians were murdered before Manila could be liberated.

On Feb. 13, the objective for Company A was Fort William McKinley (renamed Andrés Bonifacio in 1949). The fortifications included a dozen concrete pillboxes, which Pérez was the first to encounter. Eliminating them one by one was a task that seemed tougher with each advance. Pérez managed to clear the first 10, but encountered resistance in the 11th — with the private engaging and killing five Japanese in the open before moving up toward the last emplacement.

The defenses of the 12th included two twin-mount .50-caliber machine guns and this was enough to stop the paratroops in its tracks... until Pérez decided to take matters into his own hands, as described in his citation, Pérez,

“took a circuitous route to within 20 yards of the position, killing four of the enemy in his advance. He threw a grenade into the pillbox, and, as the crew started withdrawing through a tunnel just to the rear of the emplacement, shot and killed four before exhausting his clip. He had reloaded and killed four more when an escaping Jap threw his rifle with fixed bayonet at him. In warding off this thrust, his own rifle was knocked to the ground. Seizing the Jap rifle, he continued firing, killing two more of the enemy. He rushed the remaining Japanese, killed three of them with the butt of the rifle, and entered the pillbox, where he bayoneted the one surviving hostile soldier. Singlehandedly, he killed 18 of the enemy in neutralizing the position that had held up the advance of his entire company.”

The 511th PIR resumed its advance to clear Manila and into the hinterlands, with Pérez usually the vanguard. On March 14, however, as A Company was making its way toward Santo Tomas, the 22-year-old was shot in the chest by a sniper and died shortly afterward.

On Dec. 27, Pérez was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, as well as a Bronze star and Purple Heart. His father had returned to Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, by then, and the medal’s presentation to Manuel Sr. had to be arranged at the International Bridge on Feb. 22, 1946. Pérez’s remains, however, were interred in the Fairlawn Cemetery in his hometown of Oklahoma City. His name lives on in Little Village Square School in Chicago and the Manuel Perez Jr. Reserve Center in Oklahoma City.

Navy leader wants to move faster, leaner instead of turning to carriers in crisis

Adm. Daryl Caudle wants to convince commanders to use smaller, newer assets for missions instead of consistently turning to huge aircraft carriers.

The U.S. Navy’s top uniformed officer wants to convince commanders to use smaller, newer assets for missions instead of consistently turning to huge aircraft carriers — as seen now in the American military buildups off Venezuela and Iran.

Adm. Daryl Caudle’s vision — what he calls his “Fighting Instructions” — calls for the Navy to deploy more tailored groups of ships and equipment that would offer the sea service more flexibility to respond to crises as they develop.

The new strategy comes as the Trump administration has moved aircraft carriers and other ships to regions around the world as concerns have cropped up, often disrupting standing deployment plans, scrambling ships to sail thousands of miles and putting increasing strain on vessels and equipment that are already facing mounting maintenance issues.

The world’s largest aircraft carrier, the USS Gerald R. Ford, was redirected late last year from the Mediterranean Sea to the Caribbean Sea, where the crew ultimately supported last month’s operation to capture then-Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. And two weeks ago, the USS Abraham Lincoln arrived in the Middle East as tensions with Iran rise, having been pulled from the South China Sea.

In a recent interview with The Associated Press before the document’s rollout, Caudle said his strategy would make the Navy’s presence in regions like the Caribbean much leaner and better tailored to meet actual threats.

Caudle said he’s already spoken with the commander of U.S. Southern Command, which encompasses the Caribbean and Venezuela, “and we’re in negotiation on what his problem set is — I want to be able to convey that I can meet that with a tailored package there.”

Admiral sees a smaller contingent in the Caribbean in the future

Speaking broadly, Caudle said he envisions the mission in the Caribbean focusing more on interdictions and keeping an eye on merchant shipping.

The U.S. military has already seized multiple suspicious and falsely flagged tankers connected with Venezuela that were part of a global shadow fleet of merchant vessels that help governments evade sanctions.

“That doesn’t really require a carrier strike group to do that,” Caudle said, adding that he believes the mission could be done with some smaller littoral combat ships, Navy helicopters and close coordination with the Coast Guard.

The Navy has had 11 ships, including the Ford and several amphibious assault ships with thousands of Marines, in South American waters for months. It is a major shift for a region that has historically seen deployments of one or two smaller Navy ships.

“I don’t want a lot of destroyers there driving around just to actually operate the radar to get awareness on motor vessels and other tankers coming out of port,” Caudle said. “It’s really not a well-suited match for that mission.”

Turning to drones or robotic systems

To compensate, Caudle envisions leaning more heavily on drones or other robotic systems to offer military commanders the same capabilities but with less investment from Navy ships. He acknowledges this will not be an easy sell.

Caudle said even if a commander knows about a new capability, the staff “may not know how to ask for that, integrate it, and know how to employ it in an effective way to bring this new niche capability to bear.”

“That requires a bit of an education campaign here,” he later added.

President Donald Trump has favored large and bold responses from the Navy and has leaned heavily toward displays of firepower.

Trump has referred to aircraft carriers and their accompanying destroyers as armadas and flotillas. He also revived the historic battleship title for a planned type of ship that would sport hypersonic missiles, nuclear cruise missiles, rail guns and high-powered lasers.

If built, the proposed “Trump-class battleship” would be longer and larger than the World War II-era Iowa-class battleships, though the Navy has not only struggled to field some of the technologies that Trump says will be aboard but it has had challenges building even smaller, less sophisticated ships on time and on budget.

Given this trend, Caudle said if the Lincoln’s recent redeployment to the Middle East were to happen under his new plan, he would talk with the Indo-Pacific commander about how to compensate for the loss.

“So, as Abraham Lincoln comes out, I’ve got a three ship (group) that’s going to compensate for that,” Caudle suggested as an example.

Caudle argues that his vision already is in place and working in Europe and North America “for the last four or five years.”

He said this could apply soon in the Bering Strait, which separates Russia and Alaska, noting that “the importance of the Arctic continues to get more and more prevalent” as China, Russia and the U.S. prioritize the region.

Trump has cited the threat from China and Russia in his demands to take over Greenland, the Arctic island overseen by NATO ally Denmark.

Caudle said he knows he needs to offer the commanders in that region “more solutions” and his “tailored force packages would be a way to get after that.”

Marine earns service’s highest non-combat award for vehicle rescue

With the driver stuck, the doors locked and the vehicle quickly filling with water, the Marine began bashing the windshield open with a hammer.

A U.S. Marine was awarded the service’s highest non-combat award on Feb. 6 for heroic actions in 2024, when he saved another Marine’s life following a motor vehicle accident.

Staff Sgt. Billy Scafidel, an armory chief with the 7th Engineer Support Battalion in the 1st Marine Logistics Group, received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal during a ceremony at Camp Pendleton, California, according to a release.

On Sept. 1, 2024, Scafidel was working outside of his home near the installation’s Del Mar Boat Basin when he heard a loud splash in the ocean.

Upon investigating the sound, he discovered a truck lying on its side, half submerged in the water, after the driver lost control of the vehicle, according to the release.

Scafidel quickly enlisted the help of a nearby friend, Hospital Corpsman 2nd Class Andrew James, then grabbed a hammer before returning to the scene, according to the release.

At the site of the accident, the pair saw an individual inside in imminent danger of drowning. The driver was stuck in the seat, the doors were locked and the driver’s side of the vehicle was quickly filling with water.

“In the moment, the only thing I was worried about was getting him out of that truck as quickly as possible,” Scafidel said in the release.

The Marine used the hammer to quickly smash the front windshield of the vehicle and create an opening for the individual trapped inside, per the statement.

As Scafidel continued to break the windshield, a military police officer, Sgt. Jason Baughman with Provost Marshall’s Office, Marine Corps Installations West, arrived and aided Scafidel.

Scafidel and Baughman broke the windshield further to create ample space for Scafidel to reach through and pull the driver from the crash onto the shore’s bank, the release states.

Before ensuring the driver received medical attention, Scafidel dived back into the water to confirm no other passengers were in the truck.

The driver was transported to a nearby naval hospital, where he made a full recovery.

“In the face of adversity when a life was on the line, Staff Sgt. Scafidel, without care for his own safety, put himself in a position to make a difference,” Marine Corps 1st Sgt. Marc McGlothlin, a senior leader of HNS Company, 7th Engineer Support Battalion, 1st Marine Logistics Group, said in the release.

The fire department’s personnel assessed Scafidel for injuries after the rescue, finding his hands were “bleeding and shredded,” the memo reads.

Scafidel, however, said he couldn’t feel anything at the time and didn’t realize his hands were severely cut, the release says.

The statement says the award was bestowed on Scafidel in recognition of his “selflessness and valor” in saving a Marine’s life.

US military boards sanctioned oil tanker in Indian Ocean

The Pentagon’s statement on social media did not say whether the ship was connected to Venezuela, which faces U.S. sanctions on its oil.

U.S. military forces boarded a sanctioned oil tanker in the Indian Ocean after tracking the ship from the Caribbean Sea, the Pentagon said Monday.

The Pentagon’s statement on social media did not say whether the ship was connected to Venezuela, which faces U.S. sanctions on its oil and relies on a shadow fleet of falsely flagged tankers to smuggle crude into global supply chains.

However, the Aquila II was one of at least 16 tankers that departed the Venezuelan coast last month after U.S. forces captured then-President Nicolás Maduro, said Samir Madani, co-founder of TankerTrackers.com. He said his organization used satellite imagery and surface-level photos to document the ship’s movements.

According to data transmitted from the ship on Monday, it is not currently laden with a cargo of crude oil.

The Aquila II is a Panamanian-flagged tanker under U.S. sanctions related to the shipment of illicit Russian oil. Owned by a company with a listed address in Hong Kong, ship tracking data shows it has spent much of the last year with its radio transponder turned off, a practice known as “running dark” commonly employed by smugglers to hide their location.

U.S. Southern Command, which oversees Latin America, said in an email that it had nothing to add to the Pentagon’s post on X. The post said the military “conducted a right-of-visit, maritime interdiction” on the ship.

“The Aquila II was operating in defiance of President Trump’s established quarantine of sanctioned vessels in the Caribbean,” the Pentagon said. “It ran, and we followed.”

The U.S. did not say it had seized the ship, which the U.S. has done previously with at least seven other sanctioned oil tankers linked to Venezuela.

Since the U.S. ouster of Maduro in a surprise nighttime raid on Jan. 3, the Trump administration has set out to control the production, refining and global distribution of Venezuela’s oil products. Officials in President Donald Trump’s Republican administration have made it clear they see seizing the tankers as a way to generate cash as they seek to rebuild Venezuela’s battered oil industry and restore its economy.

Trump also has been trying to restrict the flow of oil to Cuba, which faces strict economic sanctions by the U.S. and relies heavily on oil shipments from allies like Mexico, Russia and Venezuela.

Since the Venezuela operation, Trump has said no more Venezuelan oil will go to Cuba and that the Cuban government is ready to fall. Trump also recently signed an executive order that would impose a tariff on any goods from countries that sell or provide oil to Cuba, primarily pressuring Mexico because it has acted as an oil lifeline for Cuba.

Meet the pilots executing the rare Navy-Air Force Super Bowl flyover

The flyover is set to include two B-1s, two F-15C Eagles and a pair each of Navy F/A-18 Super Hornets and F-35C Joint Strike Fighters.